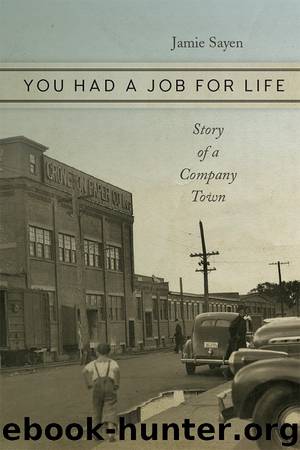

You Had a Job for Life by Jamie Sayen

Author:Jamie Sayen

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: University Press of New England

THE DEMOCRAT’S HEADLINE on October 25, 1973, read: “Fuel Reserves Dwindle at Groveton; Mill Shutdown Narrowly Averted.” The mill used sixty thousand to eighty thousand gallons of fuel oil a day, and the oil tanker carrying the mill’s resupply had been delayed at sea. When the tanker reached Portland, Maine, the oil was speedily delivered mere hours before the mill would have run out.8 This was the first hint of the oil crisis that fall and winter. Middle Eastern oil-producing nations had set up an embargo against countries that had supported Israel during the October 1973 Yom Kippur War. The price of crude oil increased by 70 percent as OPEC nations moved to secure a much greater share of the revenues from their massive oil reserves. By January 1974, oil prices had quadrupled. The era of cheap energy, one of the cornerstones of postwar American economic growth and prosperity, had expired. Skyrocketing and unpredictable energy prices would torment the energy-intensive Groveton mill for the remainder of its existence.

On December 3, 1973, the mill learned that its fuel supplier, Texaco, would reduce Groveton’s allotment for the month by 75 percent because of OPEC cuts in supply. “It was serious, really serious,” Jim Wemyss reflected. “I wasn’t sure we were going to survive. Paragon [a subsidiary of Texaco], who was selling us all our oil, told us, ‘We haven’t got any.’ I said, ‘You can’t do that to me. We’ve been with you for so many years.’ I went to military school with a fellow who was a vice president of Texaco in later years. I went down to the Chrysler Building and said, ‘I want to see him.’ ‘You have to have an appointment.’ ‘Just give him my name, and tell him I want to see him.’ I did see him, and I got my oil [laughs].”

Spurred by the 1973–1974 oil crisis, Wemyss decided to convert one of the mill’s recovery boilers to an incinerator that would generate some energy for the mill by burning mill waste and town garbage. A ton of garbage burned in an incinerator yielded the equivalent of sixty-three gallons of oil and saved the town fifteen dollars in sanitary landfill fees.9 The $250,000 incinerator began operations in October 1975.

Two or three times a day truckloads of mill trash, skids, and bad rolls of paper were delivered to the incinerator; on Wednesday and Thursday afternoons, town trash was delivered. “When they put it in, they said you could burn everything, don’t even have to separate the glass,” Thurman Blodgett, one of the incinerator crew members, said. “But every Monday morning, we had to go in with a jackhammer. It melted up front, but when it got to where it dropped down on the chain, it cooled. It solidified right there and kept building back. We’d spend all Monday, four of us, digging it out. It was shut down over the weekend. It was still hotter ’n a devil.” The incinerator experiment ended in the early 1980s. By

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Africa | Americas |

| Arctic & Antarctica | Asia |

| Australia & Oceania | Europe |

| Middle East | Russia |

| United States | World |

| Ancient Civilizations | Military |

| Historical Study & Educational Resources |

Cat's cradle by Kurt Vonnegut(15362)

Pimp by Iceberg Slim(14519)

4 3 2 1: A Novel by Paul Auster(12398)

Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt(12100)

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12033)

Wiseguy by Nicholas Pileggi(5791)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5452)

Perfect Rhythm by Jae(5409)

American History Stories, Volume III (Yesterday's Classics) by Pratt Mara L(5310)

Paper Towns by Green John(5194)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(5012)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4965)

The Mayflower and the Pilgrims' New World by Nathaniel Philbrick(4506)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4492)

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI by David Grann(4449)

The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen(4396)

Too Much and Not the Mood by Durga Chew-Bose(4349)

The Borden Murders by Sarah Miller(4329)

Sticky Fingers by Joe Hagan(4204)